On January 23, 2026, fifty thousand people marched through Minneapolis in temperatures that dropped to minus twenty degrees Fahrenheit. More than seven hundred businesses closed in solidarity. One hundred clergy members knelt on the frozen tarmac at Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport, singing hymns until they were arrested, calling on airlines to stop facilitating deportation flights. In Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania, demonstrators gathered at Citizens Bank branches to demand that the bank stop financing private prison companies. In Colorado and Texas, communities rallied against proposed detention facilities. Faith leaders, labor unions, immigrant and human rights organizations, educators, veterans, civic and business leaders – everyday Americans – are building the infrastructure of refusal.

What’s unfolding in America’s streets in January 2026 is not new. It is the latest chapter in a tradition of resistance that stretches back through centuries of Black liberation struggle, a tradition that has always understood a fundamental truth: systems of oppression require economic complicity, and withdrawing that complicity can bring those systems down. Mass surveillance, detention, incarceration, and deportation systems depend on our participation. Our deposits. Our investments. Our pension funds. Our 401(k)s. The capital that enables the expansion of detention infrastructure flows through financial institutions that manage our money.

Nearly every investor, whether they know it or not, is implicated, and for mission-driven and socially-conscious investors, the question is no longer whether to divest from these industries but how quickly they can act. Building a more just future, ensuring human rights, and preserving American democracy depend on swift, courageous action.

Defining the “Carceral Apparatus”

This broader carceral apparatus includes the “prison industrial complex” and the “deportation industrial complex,” systems where profit motives have become inextricably tangled with policies that determine who gets detained, surveilled, and removed from society. This sprawling network means that comprehensive divestment requires looking beyond the most obvious culprits to examine the full range of companies whose revenue depends on the continued expansion of detention, surveillance, and deportation. Investment screening tools that focus narrowly on private prison operators miss significant exposure to the carceral apparatus.

Today, the carceral apparatus has sprawled into something the architects of earlier movements could scarcely have imagined. Banks finance the construction of new detention beds. Logistics companies and airlines transport detainees. Healthcare contractors, food service companies, and commissary operators all extract profit from human detention. The entire architecture of surveillance, detention, and deportation has become increasingly privatized and financialized. The numbers paint a bleak picture.

Private Prisons & Detention Centers

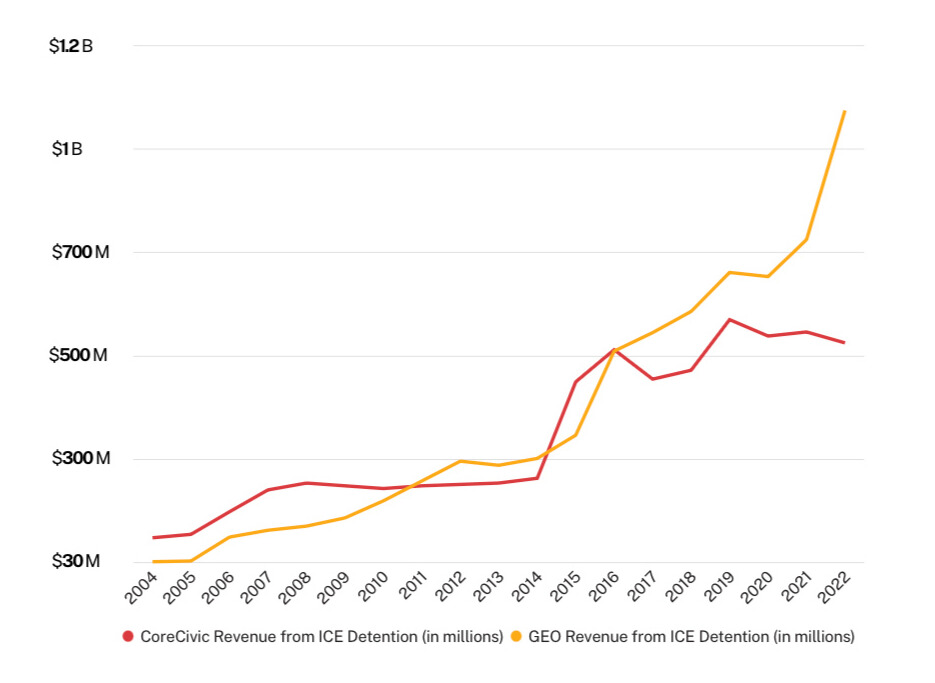

Private prison and detention operators such as CoreCivic and GEO Group operate detention facilities across the country. By 2017, about 71% of people in ICE custody were held at private facilities, a number that has only grown as the current administration has expanded detention operations.[1] ICE’s exclusion from the 2021 Biden administration’s executive order to phase out federal use of private prisons meant that private prison companies could continue to profit from immigrant detention even as their role in the criminal justice system faced restrictions.[2] The election of Donald Trump to a second term in 2024 triggered an immediate surge in private prison company stock prices. The day after the election, GEO Group’s shares jumped 41% and CoreCivic’s rose nearly 29%. Their executives were clear about why: the administration’s promise of mass deportations represented unprecedented business opportunities.

In December 2024, GEO Group announced that it had reactivated four facilities with a total of 6,600 beds for ICE, facilities that the company expects will produce more than $240 million annually. GEO’s detention centers currently house about 20,000 of ICE’s estimated 57,000 detainees, with the company advertising nearly 6,000 additional idle beds available.[3] CoreCivic has informed ICE that it has approximately 30,000 more beds that it can make available, including 13,400 beds across nine empty corrections and detention facilities. The Dilley, Texas, facility exemplifies this expansion. Originally constructed as the South Texas Family Residential Center to house families, it was closed in 2024 after President Biden phased out family detention. In 2025, CoreCivic signed an agreement with ICE to reopen the 2,400-bed facility, where fathers are typically separated from mothers and children. Annual revenue, once fully operational, is expected to reach $180 million.[4]

In spite of massive civic pushback and rebuke, private detention executives are celebrating on earnings calls that they “have never seen demand like this.” GEO Group reported $636.2 million in second-quarter revenue for 2025, a 4.8% increase from the previous year.[5] CoreCivic announced $538.2 million in quarterly revenue, up 9.8%.[6]

“Never in our 42-year company history have we had so much activity and demand for our services as we are seeing right now,” CoreCivic CEO Damon Hininger told shareholders in May 2025.[7] “Our business is perfectly aligned with the demands of this moment,” he added during an August earnings call. “We are in an unprecedented environment with rapid increases in federal detention populations nationwide and a continuing need for solutions we provide.”[8] GEO Group Executive Chairman George Zoley was equally enthusiastic. “We’ve never seen anything like this before,” he said during an earnings call in late 2025. “Our existing facilities are on full throttle.”[9] The company announced plans to invest $70 million in capital expenditures to expand its ICE services capabilities.[10]

Technology

Technology companies provide the infrastructure for e-carceration through ankle monitors, surveillance and private information aggregation, and GPS tracking systems. Palantir exemplifies how technology companies profit from surveillance and enforcement. The company’s software enables ICE to track individuals, coordinate raids, and manage detention operations. Its “Gotham” and “Foundry” operating systems have enabled surveillance of Americans by ICE and, according to reports, of Palestinians by the Israeli military. Palantir’s involvement extends beyond immigration enforcement to include partnerships with police departments, defense agencies, and intelligence services worldwide. Palantir’s total revenue surpassed $1 billion for the first time in a single quarter, with U.S. government revenue climbing 53% year over year.[11] In the third quarter of 2025 alone, ICE paid Palantir $51 million for its surveillance tools and software. Other technology companies face similar scrutiny. Amazon provides cloud computing services through Amazon Web Services that support various government agencies. Microsoft holds contracts with ICE and defense agencies. Dell provides hardware and IT infrastructure. Motorola Solutions supplies communications equipment to law enforcement and detention facilities.

Other Related “Linking” Industries

Logistics companies like UPS and FedEx handle package delivery for ICE facilities. Airlines transport detainees during deportation operations. Hotels, notably Hilton, lodge ICE agents. Healthcare contractors provide medical services in detention centers, services that investigations have found inadequate in facilities where medical neglect contributes to preventable deaths. Food service companies supply meals to detention facilities operating at the lowest possible cost, leading to reports of detainees lacking access to adequate food or water. Commissary operators profit from marking up basic goods sold to detained individuals who cannot obtain necessities any other way.

A Brief Timeline of the Private Prison Divestment Milestones

The prison divestment movement in America traces its roots to 2011, when Freedom to Thrive (formerly Enlace) launched the Prison Industry Divestment Campaign after years of strategic research on mass incarceration and deportations.[1] The campaign drew deliberate inspiration from the Anti-Apartheid divestment movement of the 1980s, which successfully pressured universities, corporations, and governments to withdraw financial support from South Africa’s brutal system of racial segregation.

- In 2008, Freedom to Thrive began following the money involved in the deportation pipeline. Their investigation into Arizona’s “Show Me Your Papers” law, SB 1070, uncovered deep connections between the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and prison profiteer Corrections Corporation of America. This research revealed how private prison corporations played a powerful role in pushing policy, infiltrating the criminal justice system, and funding political candidates.[2]

- The movement’s first major victory came quickly. In 2011, Freedom to Thrive organized a protest at the home of Bill Ackman, CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management. Within a week, Pershing divested its prison stock (approximately 7 million shares worth $180-200 million), and CCA stock subsequently dropped 21% by year’s end.[3]

- The breakthrough moment arrived in 2015 when Columbia University became the first institution of higher education in the country to divest its $9.2 billion endowment from private prisons.[4] This victory, driven by Black-led student organizing, opened the floodgates. The budding Black Lives Matter movement had brought to public prominence the link between mass incarceration and the brutal overpolicing of Black communities across the United States.

- The years 2015 through 2019 marked a period of cascading victories. Universities, like the University of California system, announced divestment plans and formally divested from private prisons. New York City completed the first-in-the-nation divestment from private prison companies by its pension funds in June 2017.[5]

- State governments joined the movement. Rhode Island divested its state pension funds from private prisons. New York passed legislation prohibiting state-chartered banks from investing in and providing financing to private prisons, a move designed to prevent regional banks from filling the void left by major financial institutions.

- The banking and financial services industry began to respond. By mid-2019, eight major banks had announced plans to end financing for private prison companies: JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, SunTrust (now Truist), BNP Paribas, Fifth Third, PNC, and Barclays. CoreCivic and GEO Group faced an estimated 87.4% financing gap as a result.[6]

Acknowledging the Connection to Black-Led Justice Movements

In 1955, Black residents of Montgomery, Alabama, launched a 381-day bus boycott of the city’s transit system and catalyzed the modern civil rights movement. In the 1960s, Reverend Leon Sullivan’s selective patronage campaigns in Philadelphia opened tens of thousands of jobs to Black workers by organizing four hundred ministers to direct three hundred thousand people away from discriminatory businesses. In 1984, protesters began daily demonstrations at the South African embassy in Washington, with more than five thousand Americans eventually arrested, until Congress overrode President Reagan’s veto to pass the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act. At each turning point, economic resistance proved decisive.

The prison divestment movement that emerged in 2011 drew explicit inspiration from this lineage. When Freedom to Thrive (then Enlace) launched the Prison Industry Divestment Campaign, organizers studied how anti-apartheid activists had used divestment as a tool of international solidarity. When Black-led student organizing won Columbia University’s divestment from private prisons in 2015, it echoed the victories of student activists who had forced universities to divest from South Africa three decades earlier. When the Movement for Black Lives released its Invest-Divest platform in 2016, it placed the demand to divest from prisons, police, and surveillance at the center of a comprehensive vision for Black liberation.

The throughline is clear. From mutual aid societies purchasing freedom for enslaved people, to Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line, to Operation Breadbasket’s campaigns for economic justice, to TransAfrica’s anti-apartheid organizing, Black Americans have consistently recognized that liberation requires disrupting the flow of capital to oppressive systems. Each generation has built on the victories of the last, transferring knowledge and tactics forward. Leon Sullivan’s selective patronage informed Dr. King’s economic strategies. Anti-apartheid divestment tactics directly shaped the prison divestment movement. The work continues.

Shareholder Value & Human Collateral

While executives celebrate record revenues, the human toll mounts. The 2025 fiscal year became one of the deadliest for detainees in ICE custody, with at least 23 to 32 deaths reported across the country.[1] An investigation released by Senator Jon Ossoff uncovered that from January to August 2025, there were 85 credible reports of medical neglect and 82 credible reports of detainees lacking access to adequate food or water.[2]

The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse found that ICE has been transferring detainees far from their arrest locations, often to private facilities operating over their contractual capacity. On April 13, 2025, 45 of ICE’s 181 facilities were overfilled, with several exceeding limits by more than 100 people. Overcrowded sites were predominantly run by private contractors such as GEO Group and CoreCivic.[3]

These conditions are not accidental. They are the predictable outcome of a system designed to maximize profit. As immigration advocate Setareh Ghandehari of the Detention Watch Network explained, “A for-profit company, by definition, is trying to make money on this whole process. What we’re witnessing right now is a multilayered detention expansion plan that includes proliferating ICE operations into other government agencies, using military bases as deportation hubs, deepening ties with private prison companies, and growing ICE partnerships with local sheriffs and county jails.”[4]

The CoreCivic-operated Cibola Correctional Facility in New Mexico exemplifies the dangers. The facility is currently under FBI investigation for drug trafficking and has seen at least 15 deaths since 2018. [1] CoreCivic has spent more than $4.4 million since 2016 to settle dozens of mistreatment complaints at its Tennessee facilities.[2]

Annual Revenue for Prison Companies with the Largest ICE Detention Contracts

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission data; ACLU analysis; Cited in Natural Investments PBLLC article

The investment case against private prisons extends well beyond CoreCivic and GEO Group. The entire carceral apparatus includes electronic monitoring companies, commissary contractors, medical service providers, and surveillance technology firms each face the same fundamental risk: their revenues depend on detained and monitored people, creating exposure to criminal justice policy shifts, immigration enforcement changes, and evolving public sentiment about mass incarceration.

That sentiment is shifting for good reason. The United States spends over $80 billion annually on incarceration alone, with state and local governments spending an additional $100 billion on police and courts. This works out to roughly $35,000 per incarcerated person per year on average, though costs vary wildly by state, but we know that the economic damage extends far beyond direct spending. Incarceration removes workers from the labor force, with 70 million Americans now carrying criminal records that create barriers to employment, housing, and education. The Ella Baker Center found that 63% of families with incarcerated members could not meet basic needs, and family members on the outside take on an average of $13,000 in debt related to court fees, phone calls, commissary, and travel for visits. These costs fall disproportionately on Black and Latino communities, where incarceration rates are 5 to 6 times higher than for white Americans despite similar rates of criminal behavior. The result is generational wealth extraction from communities already facing systemic economic disadvantage.

Human and civil rights violations in these facilities create quantifiable financial damage for the companies involved. When CoreCivic faced allegations of sexual abuse and inadequate medical care at its Dilley, Texas detention center in 2015, the company’s stock dropped 8% within weeks. GEO Group has paid out millions in wrongful death settlements, including a $1 million payout in 2021 for Roxsana Hernández Rodriguez’s death in ICE custody. A 2016 Justice Department report found private prisons had higher rates of assaults compared to Bureau of Prisons facilities. The reputational and legal costs ripple through supply chains as technology companies providing biometric scanning or predictive policing face similar blowback when investigations link their systems to discriminatory enforcement.

The cloud Automatic License Plate Reader (ALPR or LPR) company Flock Safety, which was founded in Georgia in 2017 and maintains physical locations across the state, is a growing concern per the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The ACLU asserts that Flock epitomizes the dangers posed by hybrid public-private surveillance practices, and as ICE escalates immigration enforcement, agents are openly stating that American observers and protesters are being filmed for future surveillance. In Minnesota, an ICE agent was captured on video saying that he was photographing ICE observers’ license plates to add to a “nice little database” of “domestic terrorist[s].”

The regulatory risk is acute and data-supported. Private prison companies lost roughly 50% of their market value between August 2016 and January 2017 after the Obama administration announced plans to phase out private prison contracts. California’s pension funds divested $400 million from private prison holdings in 2015. New York State’s pension fund divested $48 million in 2021. Between 2015 and 2020, at least 25 major institutional investors either fully or partially divested from private prison companies, representing billions in withdrawn capital. Companies providing electronic monitoring, jail communication systems, or deportation logistics face identical exposure. Their profitability requires sustained commitment to policies that cost American taxpayers billions, fail to reduce crime, and damage the economic prospects of millions of families. For long-term institutional investors, that dependence creates structural instability.

It’s for these reasons and more that foundations, public pension funds, banks and financial services companies, and investment managers have divested themselves of private prisons and other incarceration-related companies and industries.

Takeaways & Steps to Divest Now

This is the moment to make that implication visible and to act on it. The civic unrest erupting across America is one front of the struggle. The financial front is another. When universities divest their endowments, when pension funds remove private prison companies from their portfolios, when banks refuse to provide financing, when individual investors demand prison-free options in their retirement accounts, the calculus changes. Companies face higher costs of capital. Stock prices decline. The profit margins that make human detention attractive to corporate executives shrink. These dominoes can fall.

The investment decisions that institutions and individuals make today will either enable or constrain this expansion. Capital flows to where investors direct it. If private prison companies can easily access financing, they will build more facilities. If surveillance technology companies can profit from government contracts without reputational consequences, they will continue developing systems that enable mass detention and deportation. Tested tools and models for divestment exist, the pathways are proven, and the movement is growing, but Congress has approved the largest ICE budget in history. The detention infrastructure is expanding rapidly, and every day capital continues to flow is a day it becomes harder to dismantle.

The urgency is now. The people in the streets know it. The question is whether investors, individual and institutional alike, will join them. Whether we will continue to provide the capital that enables the carceral state’s expansion, or withdraw it and redirect it toward building the communities and systems that can replace it. This is not a new question. It is the same question that faced Americans asked to deposit their money in banks that financed apartheid, that faced community members asked to ride segregated buses, that faced investors asked to hold stock in companies profiting from injustice. At each of those moments, people made the choices that shaped history.

We are at such a moment now. The following pages offer a guide for those ready to act: the landscape of the carceral apparatus and its profiteers, the history and victories of the divestment movement, the practical pathways for individual and institutional investors, and the urgent reasons why the time to move is now. The tradition of economic resistance that runs through American history has brought us to this point. What we do next is up to us.