Impact Investing Terms

Are there different impact investing approaches or strategies?

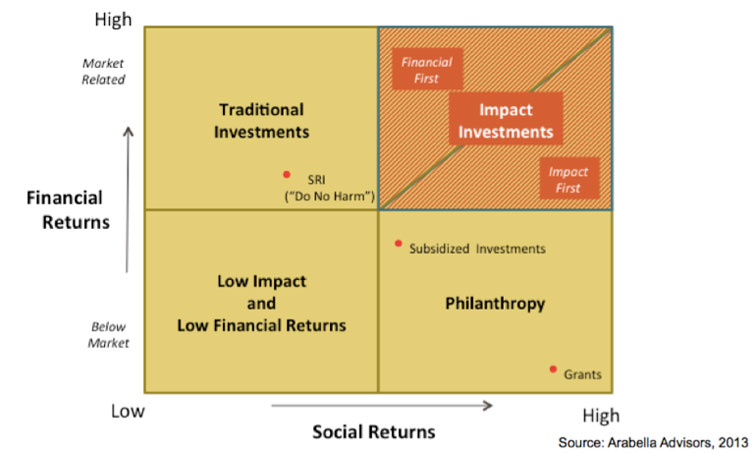

Yes, not all impact investing is the same. Impact investing is an umbrella term that encompasses different approaches and strategies.

- Divesting is the practice of selling shares or bonds in a company due to a fundamental disagreement with its business practices or when the company’s outputs are antithetical to the investors mission or values. This could look like an environmental nonprofit divesting from fossil fuel companies or a health-focused foundation divesting from tobacco and alcohol stocks. Once divested, impact investors can work with investment managers to ensure that those companies are excluded from future investment selections and allocations.

- Responsible Investing is an approach to investing that considers both financial returns and the broader social, environmental, and governance impacts of an investment. It generally seeks to promote sustainable practices, reduce harmful impacts, and support initiatives that benefit society. There are several approaches within responsible investing, with ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) investing and thematic impact investing being two common strategies. Often, responsible investing offerings (both ESG and thematic impact investing) can be facilitated by investment managers and OCIOs.

- ESG Investing focuses on integrating Environmental, Social, and Governance criteria into investment decisions. ESG investing evaluates how well companies are managing risks and opportunities related to these criteria, which can affect long-term financial performance.

- Environmental factors consider a company’s impact on natural resources, carbon emissions, waste management, and overall sustainability efforts.

- Social factors look at relationships with employees, customers, communities, and other stakeholders, including practices around diversity, equity, and community impact.

- Governance factors assess a company’s internal practices and policies, including board composition, executive compensation, and transparency.

- Thematic Impact Investing goes a step beyond ESG by actively seeking investments in companies or projects that have a direct, positive impact on specific social or environmental issues. It aligns with the investor’s intent to generate measurable, positive outcomes alongside financial returns. Thematic impact investing targets specific issues or causes, such as renewable energy, affordable housing, education, health care, or gender equality. Investments are chosen for their potential to make a direct impact in the chosen theme, meaning that the business model or operations inherently address these social or environmental challenges.

- ESG Investing focuses on integrating Environmental, Social, and Governance criteria into investment decisions. ESG investing evaluates how well companies are managing risks and opportunities related to these criteria, which can affect long-term financial performance.

- Place-Based Impact Investing occurs when those with capital invest in businesses, organizations, companies, and/or funds who will advance community impact and benefit in a specific geographic area or community. Impact investors can use place-based impact investing at many levels – a country, state, city, town, or even specific neighborhoods. Often, place-based impact investing is a strategy that excites mission-first investors because it is a promising tool for those tackling long-term, systems change work in specific communities. Place-based impact investing is generally done outside of the purview of investment managers and OCIOs. These investments sit in separately-managed pools and are overseen by staff, investment committees, boards, and specialized investment consultants.

What are common impact investing financing tools or instruments?

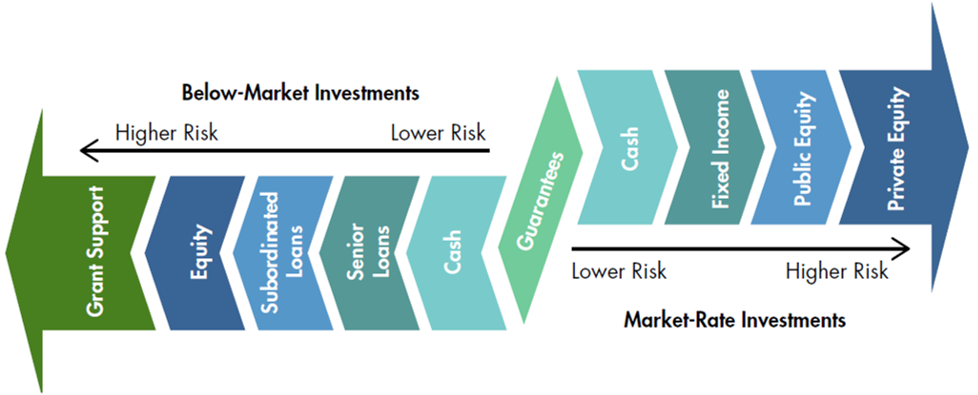

Debt or Lending: Debt, or lending, refers to a financial arrangement in which a lender provides capital to a borrower with the agreement that the borrower will repay the principal amount plus interest over a specified period. Debt instruments include loans, bonds, promissory notes, and credit lines.

- Key Characteristics:

- Repayment Obligation: Borrowers must repay the loan regardless of business performance.

- Interest Rates: The cost of borrowing is typically determined by an interest rate, which can be fixed or variable.

- Collateral: Some debt arrangements may require collateral as security for the loan.

- Regulation: Debt instruments are subject to various regulations depending on the jurisdiction and type of lender (e.g., banks, credit unions, or CDFIs).

- Purpose: Debt financing is commonly used by individuals, businesses, and governments to fund operations, capital expenditures, or growth projects. It is often chosen because it allows the borrower to retain ownership while accessing necessary capital.

- Unique Aspects: Unlike equity, debt does not confer ownership or decision-making rights to the lender. It is less risky for the borrower because the cost is predictable (interest), but it can burden cash flow due to fixed repayment schedules.

Guarantee: A guarantee is a promise by a third party (the guarantor) to assume responsibility for the debt or obligations of a borrower if the borrower defaults. Guarantees are used to reduce the risk for lenders, encouraging them to provide loans to borrowers who might otherwise be deemed too risky.

- Key Characteristics:

- Types of Guarantees: Can include personal guarantees (e.g., provided by an individual) or institutional guarantees (e.g., provided by a government or nonprofit entity). Guarantees can also be funded or unfunded.

- Risk Mitigation: Guarantees lower the risk for lenders, potentially reducing interest rates or allowing for larger loans.

- Non-Cash Instrument: A guarantee does not involve the transfer of funds unless the borrower defaults.

- Purpose: Guarantees are particularly valuable in community development or impact investing, where they enable access to capital for underserved populations or high-risk ventures. For example, government-backed guarantees through agencies like the SBA in the U.S. support small businesses.

- Unique Aspects: Guarantees stand out because they are a form of risk-sharing rather than direct financing. They encourage private investment in projects that align with public or philanthropic goals without requiring upfront capital contributions from the guarantor.

Equity: Equity represents ownership in an asset, business, or project. Investors provide capital in exchange for a proportional share of ownership, giving them the right to a portion of the entity’s profits (dividends) and a say in its management.

- Key Characteristics:

- Ownership Rights: Equity investors often have voting rights, depending on the type of equity (e.g., common or preferred stock).

- Profit Participation: Returns are tied to the entity’s performance, either through dividends or capital gains upon sale.

- No Fixed Repayment: Unlike debt, equity does not require repayment, but it does dilute the original owner’s stake.

- Purpose: Equity financing is typically used for long-term growth, innovation, or large-scale projects. It is common among startups, high-growth companies, and community development projects that need patient capital.

Unique Aspects: Equity is riskier for investors because returns depend entirely on the entity’s success. However, it offers higher potential rewards than debt. Unlike debt or guarantees, equity aligns the interests of the investor and the entity, as both benefit directly from financial success.

What are Capital Aggregators, and how do they relate to local investment ecosystems?

Capital Aggregators are vital pieces of local capital ecosystems. Capital Aggregators can be local community development financial institutions (CDFI), credit unions, community development corporations (CDC), revolving loan funds (RLF), angel or venture funds, or even local bank branches. Capital Aggregators are professional investment organizations who raise capital from various sources (like foundations, government, banks) and make investments – often by investing in affordable and workforce housing, community real estate projects, local small businesses and enterprise, and more.

- Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs): CDFIs are specialized financial institutions certified by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to serve low-income, underserved, and economically distressed communities. They provide access to affordable credit, capital, and financial services to populations and businesses that traditional financial institutions may overlook. CDFIs include banks, credit unions, loan funds, and venture capital funds, all of which focus on fostering community development and reducing economic inequity. They are unique because they blend social mission with financial discipline, aiming to generate measurable social impact alongside financial returns. CDFIs differ from conventional banks by targeting borrowers who might not meet the typical credit criteria and often providing technical assistance to ensure borrowers’ success. Their funding comes from a mix of federal programs, private investors, and philanthropic contributions.

- Community Development Corporations (CDCs): CDCs are nonprofit, community-based organizations focused on improving the economic, physical, and social conditions in low-income neighborhoods. Legally structured as 501(c)(3) organizations, CDCs are distinct in their mission-driven approach to revitalizing communities. They often engage in projects such as affordable housing development, workforce training, small business support, and infrastructure improvement. CDCs are unique because they are rooted in the communities they serve, often governed by a board of directors composed of local residents, business owners, and other stakeholders. Unlike CDFIs, CDCs do not necessarily provide direct financial services but instead focus on implementing and managing development projects. Many CDCs work in partnership with CDFIs or local governments to secure funding for their initiatives.

- Banks and Depository Institutions: Banks and depository institutions are financial entities authorized by regulatory agencies, such as the Federal Reserve or FDIC in the U.S., to accept deposits, make loans, and provide other financial services. They serve as the backbone of the financial system, facilitating economic activity by safeguarding savings and offering credit to consumers and businesses. What makes them unique is their dual role in serving the public (e.g., consumer banking) and acting as intermediaries in capital markets. Unlike CDFIs or CDCs, traditional banks often prioritize profit over social impact and may not focus on underserved communities unless required by regulations such as the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). CRA encourages banks to meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, sometimes leading banks to partner with CDFIs or CDCs.

- Revolving Loan Funds (RLFs): Revolving Loan Funds are pools of capital established to provide loans for specific purposes, such as small business development, community projects, or environmental initiatives. As borrowers repay the loans, the repayments replenish the fund, allowing it to issue new loans. RLFs are often created by governments, nonprofits, or community organizations and may focus on economic development, disaster recovery, or sustainability goals. RLFs are unique because they are self-sustaining once established, relying on loan repayments rather than continual external funding. Unlike CDFIs or traditional banks, RLFs typically have more flexible lending terms and may target a niche audience, such as minority-owned businesses or startups in economically distressed areas.

What do the terms "PRI" and "MRI" mean?

Program-Related Investments (PRIs) and Mission-Related Investments (MRIs) are tools used by private foundations to align their financial activities with their charitable purposes, but they are distinct in their purposes, regulatory treatment, and financial expectations. These mechanisms are not typically applicable to public charities due to differences in tax treatment and operational priorities.

Program-Related Investments (PRIs): PRIs are investments made by private foundations to advance their charitable purposes while allowing the potential for a financial return, although financial gain is secondary to achieving the foundation’s mission. PRIs are recognized under the U.S. tax code and must meet specific criteria to qualify:

- Primary Purpose: The investment must significantly further the foundation’s charitable mission.

- No Significant Financial Purpose: Generating financial returns cannot be a primary motivation.

- Charitable Intent: The investment must not be made to influence legislation or political campaigns.

Examples of PRIs include low-interest loans to nonprofits, equity investments in social enterprises, or funding for affordable housing projects. PRIs count toward the foundation’s annual 5% distribution requirement for charitable activities, making them an attractive way to align investments with philanthropic goals.

Mission-Related Investments (MRIs): MRIs are investments that align with a foundation’s mission while seeking market-rate or near-market-rate financial returns. Unlike PRIs, MRIs are part of a foundation’s endowment and are not subject to the same strict IRS requirements. They serve a dual purpose:

- Financial Performance: MRIs aim for financial returns comparable to traditional investments.

- Mission Alignment: MRIs prioritize investments in industries or projects aligned with the foundation’s social or environmental goals, such as ESG funds, renewable energy projects, or community development loans.

While MRIs don’t count toward the 5% distribution requirement, they allow foundations to leverage their endowment to advance their missions more broadly than grants or PRIs alone.

What are the common sources of public and private capital that make local impact investments happen in communities?

- Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is intended to encourage banks to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate. It requires that each institution’s record in meeting the credit needs of its entire community be evaluated periodically. Qualifying activities include: investing in Community Development Entities (CDEs) and Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), supporting minority- and women-owned financial institutions and low-income credit unions (MWLIs), serving as a joint lender for a loan originated by MWLIs, facilitating financial literacy education to low-income communities, operating branches in low-income communities, providing low-cost education loans to low-income borrowers and offering international remittance services in low-income communities. CRA is associated with a degree of controversy due to higher-priced loan products possibly receiving CRA credit, but it also facilitates significant small business lending and community development in MWLI communities.

- Bank Enterprise Award Program (BEA Program): The CDFI Fund provides monetary awards to FDIC-insured depository institutions (i.e., banks and thrifts) that successfully demonstrate an increase in their investments in CDFIs or in their own lending, investing, or service activities in the most distressed communities. BEA Distressed Communities are defined as those where at least 30% of residents have incomes that are less than the national poverty level and where the unemployment rate is at least 1.5 times the national unemployment rate.

- New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) Program is run through the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund. NMTCs credits are managed through Community Development Entities (CDEs) such as Invest Atlanta affiliate Atlanta Emerging Markets, Inc. (AEMI) and provide tax credits totaling 39% of the original investment amount over a period of 7 years. NMTC projects have to be located in a designated qualified low-income community. PolicyMap can be used to determine eligibility.

- Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Program provides dollar-for-dollar tax incentives to private or nonprofit developers to create affordable housing. Tax credits are provided to states and distributed to developers by the state’s designated authority. In Georgia, the Department of Community Affairs manages its distribution. There are two types of LIHTC – 9% credits, which are typically used for new construction, and 4% credits, which are typically used for renovations – that last for 10 years.

- Opportunity Zones (OZs) were created in the 2017 tax bill and the program is awaiting final regulations from the IRS. Proposed regulations were published for comment in mid-October 2018. The roughly 9,000 OZs encompassing 35 million Americans created through the program will attract investors, if implementation is successful, by [1] deferring capital gains taxes until 2026 or withdrawal from an opportunity fund, [2] reducing capital gains taxes by 15% after a 7-year OZ investments and [3] permanently excluding new gains derived from an opportunity fund if the investment is held for 10 years.

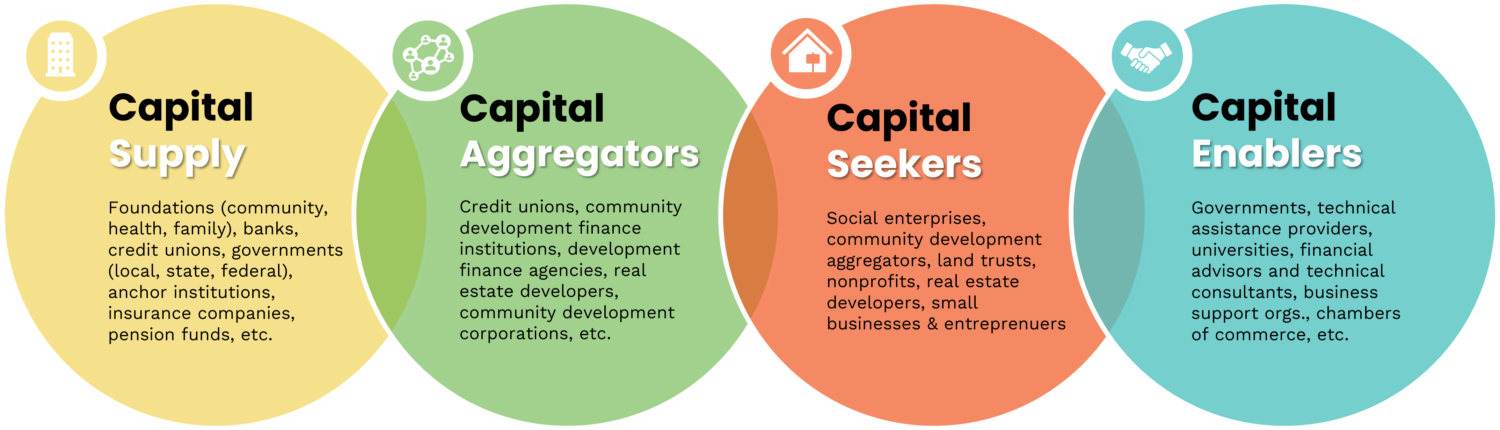

Place-Based Impact Investing Ecosystem Framework

Every community has a capital (or investment) ecosystem that determines where money flows in the economy. There are Capital Suppliers, Capital Aggregators, Capital Seekers, and Capital Enablers.

Capital Suppliers in a local impact investing ecosystem are entities or individuals that provide financial resources to fund initiatives aimed at generating both social or environmental impact and financial returns. These suppliers are critical to the ecosystem as they enable the flow of capital to projects, businesses, or organizations focused on addressing community needs and fostering equitable economic growth. The most common Capital Suppliers include:

- Philanthropic foundations provide grants, program-related investments (PRIs), or mission-related investments (MRIs) to support social enterprises or community development projects. They often prioritize impact over financial returns and align funding with their mission.

- Government agencies offer subsidies, guarantees, and funding programs through economic development initiatives. They create enabling conditions for private capital by mitigating risk (e.g., through tax credits or loan guarantees).

- Institutional investors can include pension funds, insurance companies, or university endowments. Increasingly, these investors allocate portions of their portfolios to impact investments, particularly in sustainable infrastructure, affordable housing, or ESG (environmental, social, and governance) funds.

- High-Net-Worth Individuals (HNWIs) and family offices can be wealthy individuals or families that invest in projects that align with their values, often taking higher risks in exchange for significant impact. These investors often serve as angel investors or funders of innovative community development initiatives.

- Retail investors can be individuals contributing through crowdfunding platforms, community investment notes, or local bonds. These outlets bring more grassroots-level participation into the impact investing space.

- Corporate entities are businesses providing capital through corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs, impact bonds, or direct investments in social enterprises. These organizations often aim to align community investments with business goals or brand values.

- Religious and faith-based organizations allocate financial resources to projects that align with their moral or ethical missions, such as affordable housing or healthcare initiatives.

Capital Aggregators are vital pieces of local capital ecosystems. Capital Aggregators can be local community development financial institutions (CDFI), credit unions, community development corporations (CDC), revolving loan funds (RLF), angel or venture funds, or even local bank branches. Capital Aggregators are professional investment organizations who raise capital from various sources (like foundations, government, banks) and make investments – often by investing in affordable and workforce housing, community real estate projects, local small businesses and enterprise, and more.

- Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs): CDFIs are specialized financial institutions certified by the U.S. Department of the Treasury to serve low-income, underserved, and economically distressed communities. They provide access to affordable credit, capital, and financial services to populations and businesses that traditional financial institutions may overlook. CDFIs include banks, credit unions, loan funds, and venture capital funds, all of which focus on fostering community development and reducing economic inequity. They are unique because they blend social mission with financial discipline, aiming to generate measurable social impact alongside financial returns. CDFIs differ from conventional banks by targeting borrowers who might not meet the typical credit criteria and often providing technical assistance to ensure borrowers’ success. Their funding comes from a mix of federal programs, private investors, and philanthropic contributions.

- Community Development Corporations (CDCs): CDCs are nonprofit, community-based organizations focused on improving the economic, physical, and social conditions in low-income neighborhoods. Legally structured as 501(c)(3) organizations, CDCs are distinct in their mission-driven approach to revitalizing communities. They often engage in projects such as affordable housing development, workforce training, small business support, and infrastructure improvement. CDCs are unique because they are rooted in the communities they serve, often governed by a board of directors composed of local residents, business owners, and other stakeholders. Unlike CDFIs, CDCs do not necessarily provide direct financial services but instead focus on implementing and managing development projects. Many CDCs work in partnership with CDFIs or local governments to secure funding for their initiatives.

- Banks and Depository Institutions: Banks and depository institutions are financial entities authorized by regulatory agencies, such as the Federal Reserve or FDIC in the U.S., to accept deposits, make loans, and provide other financial services. They serve as the backbone of the financial system, facilitating economic activity by safeguarding savings and offering credit to consumers and businesses. What makes them unique is their dual role in serving the public (e.g., consumer banking) and acting as intermediaries in capital markets. Unlike CDFIs or CDCs, traditional banks often prioritize profit over social impact and may not focus on underserved communities unless required by regulations such as the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). CRA encourages banks to meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, sometimes leading banks to partner with CDFIs or CDCs.

- Revolving Loan Funds (RLFs): Revolving Loan Funds are pools of capital established to provide loans for specific purposes, such as small business development, community projects, or environmental initiatives. As borrowers repay the loans, the repayments replenish the fund, allowing it to issue new loans. RLFs are often created by governments, nonprofits, or community organizations and may focus on economic development, disaster recovery, or sustainability goals. RLFs are unique because they are self-sustaining once established, relying on loan repayments rather than continual external funding. Unlike CDFIs or traditional banks, RLFs typically have more flexible lending terms and may target a niche audience, such as minority-owned businesses or startups in economically distressed areas.

- Angel or Venture Funds: Angel funds and venture funds are investment vehicles that provide capital to startups or early-stage businesses in exchange for equity or convertible debt. Angel funds are typically smaller, backed by wealthy individuals, while venture funds are institutional and often managed by professional firms. Both types of funds focus on businesses with high growth potential, often in technology, healthcare, or innovation sectors. These funds are unique because they assume higher risks than traditional lending or investment mechanisms, aiming for significant returns if the businesses succeed. They differ from CDFIs and RLFs, which focus on social impact and often provide loans, not equity. Angel and venture funds prioritize scalability and profitability rather than serving disadvantaged communities, though there are impact-focused venture funds that aim to combine financial returns with social or environmental benefits.

Capital Seekers in a local impact investing ecosystem are individuals, organizations, or entities seeking financial resources to fund projects, initiatives, or enterprises that generate both social or environmental impact and financial returns. They represent the demand side of the impact investing ecosystem and play a crucial role in driving community development and addressing local challenges. The most common Capital Seekers include:

- Social Enterprises: For-profit or hybrid businesses that address social, environmental, or community issues as part of their core mission. Examples include: Renewable energy startups, workforce development businesses, companies providing affordable healthcare solutions, etc.

- Traditional Social Service Nonprofits: Seek funding for mission-driven programs that create measurable social or environmental benefits. Often use grants, program-related investments (PRIs), below-market-rate debt, or other flexible capital sources. Examples include: Homeless shelters, food banks, childcare nonprofits, community advocacy organizations, etc.

- Community Development Nonprofits and Capital Aggregators: Community development nonprofits are nonprofit organizations dedicated to improving the social, economic, and physical well-being of underserved or economically disadvantaged communities. These organizations focus on initiatives that address systemic inequities, foster economic growth, and enhance the quality of life for residents. There is overlap between these organizations and Capital Aggregators. Capital Aggregators are professional investment organizations who raise capital from various sources (like foundations, government, banks) and make investments – often by investing in affordable and workforce housing, community real estate projects, local small businesses and enterprise, and more. Examples include: CDFIs, CDCs, land and real estate trusts, nonprofit affordable housing and commercial real estate developers, etc.

- Small Businesses and Entrepreneurs: Especially those owned by women, minorities, or individuals from underserved communities. Require working capital, equipment loans, or investment to expand operations or create jobs in local economies. Businesses and enterprises vary structurally. This Capital Seeker segment can include cooperatives, Benefit Corporations, etc. Examples include: Neighborhood grocery stores, tech startups, or artisan cooperatives.

Capital Enablers are organizations, entities, or individuals that facilitate the efficient flow of financial resources within a local impact investing ecosystem. They may or may not directly provide or seek capital but play essential roles in connecting Capital Suppliers, Capital Aggregators, and Capital Seekers – building capacity, reducing risk, and ensuring effective allocation of funds to achieve social and environmental goals alongside financial returns.

- Capacity-Building Organizations help capital seekers (like social enterprises or nonprofits) become investment-ready by offering technical assistance, business planning, and financial literacy training. Examples include: Small Business Development Centers (SBDCs) or entrepreneurial incubators.

- Networks and Conveners create platforms for collaboration and networking among stakeholders in the ecosystem, and they facilitate knowledge-sharing, partnerships, and deal-making opportunities. Examples include: Impact investing networks (like GSIC and Mission Investors Exchange) or local chambers of commerce.

- Technical Advisory and Consulting Firms Provide specialized advice to capital suppliers or seekers, including investment strategies, impact measurement, or financial structuring. Examples include: Real estate development advisors, ESG consulting firms, nonprofit financial advisors.

- Financial Advisors and Wealth Managers bridge the gap between capital suppliers (such as high-net-worth individuals, families, or institutional investors) and the projects or enterprises seeking funding. They guide clients in aligning their financial goals with their social and environmental values, facilitating the flow of capital into impact investments.

- Legal and Regulatory Advisors assist in navigating the complex legal and regulatory landscape for impact investments and support efforts to structure deals, secure tax credits, or comply with reporting requirements.

- Research and Data Organizations/Thought Leaders generate insights, market research, and impact metrics to guide decision-making in the ecosystem. Examples include: Universities, think tanks, or organizations like the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Urban Institute.

- Technology Platforms offer digital tools to streamline funding processes, track impact metrics, or connect stakeholders. Examples include: Crowdfunding platforms like Kiva, community investment portals, or financial technology tools.

- Philanthropic and Public Sector Partners Provide grants or guarantees to de-risk investments, encourage private-sector participation, or fund capacity-building initiatives. Examples include: Government agencies like the SBA or foundations offering catalytic capital.